All through the 1950s and 1960s, as I grew up in Fair Lawn, my beloved hometown in northern New Jersey, almost every one of our immediate neighbors, the dozens of families around our block and those nearby, was, like us, Jewish.

Over here, likewise housed in split-level colonials on quarter-acre plots, lived the Fishmans, the Kutners and the Broslovksys, over there the Nichterns, the Goldenbergs and the Hefflers, and around the corner, the Krakauers, Laskers, Witzburgs, Hamburgs, Solomons, Roselinskys, Klappers, Cohens, Hermans and Heymanns.

But thanks to my natural naivete as a boy, as I lived in this suburb in Bergen County, about 12 miles west of New York City, from 1954 to 1975, I never knew the truth about our adjacent neighborhood.

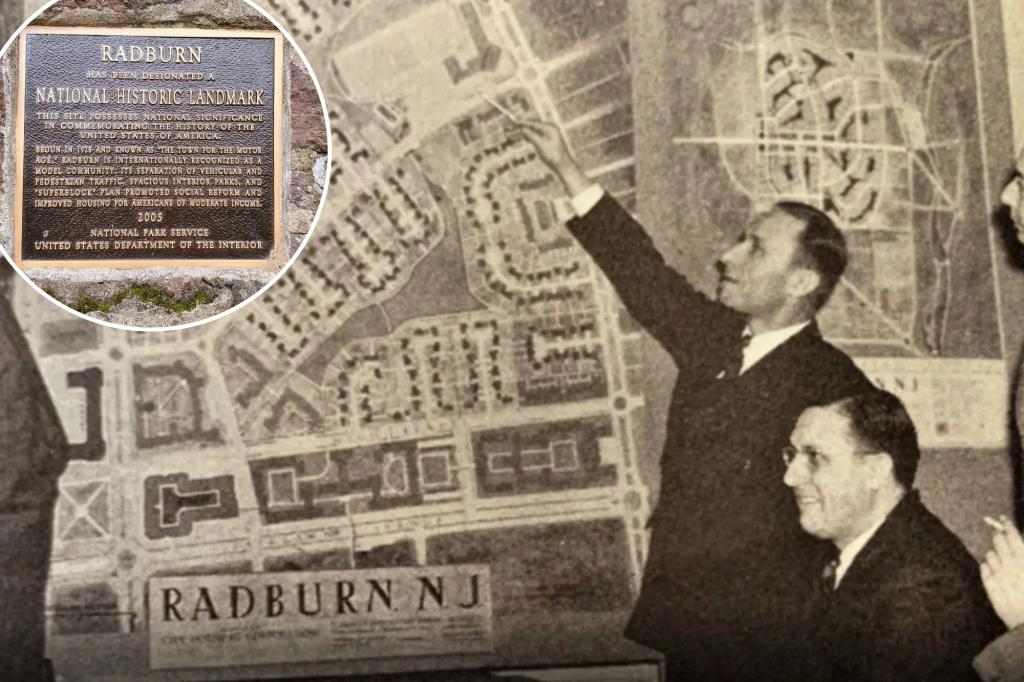

Only a block away from us, in a section of Fair Lawn called Radburn — an internationally renowned 149-acre enclave later designated a National Historic Landmark District for its innovative infrastructure — our kind were unwelcome.

Radburn — originally about two-thirds Protestant and about one-third Catholic — had systematically excluded Jews from owning homes from the 1930s to the 1950s.

This disparity felt all the more disturbing to me years later because I not only lived 200 yards from Radburn, but also lived on Radburn Road, attended Radburn Elementary School, played in Radburn parks and playgrounds and my father managed the Radburn Plaza Building, a landmark commercial property. So without actually living in Radburn, I was nonetheless very much Radburn.

This month Fair Lawn’s 100th anniversary ends, doing so against the backdrop of an unprecedented worldwide surge in antisemitism since Hamas attacked Israel over a year ago.

Over the past year, Fair Lawn has rolled out a street fair, a float for the Memorial Day parade and an oral history project. But as its 100th anniversary comes to a close, Fair Lawn has yet to acknowledge how its cherished Radburn section came under the shadow of systemic antisemitism.

“We had no Jewish people living in houses in Radburn up through the 1960s,” says Cornell Christianson, a former Radburn resident and co-author of “Legendary Locals Of Fair Lawn,” a town history. “None of the kids in my Boy Scout troop was Jewish either.”

In more than one case, Radburn residents resorted to sabotaging a Jewish couple interested in buying a house there in 1950. “The word in the neighborhood got out that a Jew and his family — my mother and father — were about to buy a house in Radburn,” says former Radburn resident Janet Moss Kass.

“Several of the families surrounding the house pooled some money, approached the seller and offered to buy the house out from under my parents in order to ‘stop Jews from moving into Radburn.’ But the seller refused, and we moved in, becoming only the second or third Jewish family there.”

Another, similar incident in the 1950s proved equally telling. “My mother told me that when she and my father originally looked in Radburn for a house to buy, the real estate broker, himself Jewish, said they would be ‘unhappy’ there,” a current Jewish Radburn resident who requested anonymity recalls.

“At the time, my parents had no idea what he meant, nor why he said it. So they followed his advice to buy a house less than 50 yards away from Radburn. They had never dealt with any prejudice — they always lived among other Jews in The Bronx — and so they never suspected any. But years later they realized that they were being deliberately excluded.”

Similarly, in March, 1953, the Schoenberg family — mother, father and two sons — moved into Radburn, among the first Jewish families then to live there. In response, six of the 16 houses on the cul-de-sac went up for sale within weeks, evidently because this Jewish family had bought a house down the block.

“Nobody knew what a Jew looked like or how we were going to act,” recalls Steve Schoenberg, then only age 3. “Were we going to ruin the neighborhood? Drive property value down? I guess people had no idea what to expect.”

Some Jewish Radburn residents today recall feeling ostracized as children in the 1950s. “A girl on our block had a birthday party and invited all her classmates except me,” says one.

Says another, “Some kids called me ‘k–e’ and ‘dirty Jew’ as I walked to school. Finally, I gave those kids bloody noses and they learned some respect.”

Such anecdotes reinforce the reality that Radburn was a microcosm of the national landscape, says Hasia R. Diner, author of “The Jews of the United States, 1654 to 2000” and director of the Goldstein-Goren Center for American Jewish History.

“What happened in Radburn was pretty common in suburbs around the country,” Diner says. “Developers were free to discriminate, but only up until about 1948, when the Supreme Court ruled that the restrictive covenants in place were unenforceable.”

Radburn’s original planner, Clarence Stein, though himself Jewish, set out to limit the number of Jews there. He envisioned Radburn as non-Jewish, but mainly because real estate interests feared that if it became ‘too Jewish,’ it would attract still more Jews and non-Jews would stay away.”

No written policy expressly banning Jews from living in Radburn ever appears to have existed. But historians and residents have identified an implicit, unspoken understanding among real estate investors that Radburn would be “restricted,” and, further, that realtors would routinely inform Jewish families seeking housing there that they might be “more comfortable” living elsewhere in town.

“Restrictive covenants for segregated housing were fairly widely used after World War I in suburban America to keep out Jews and others,” says Scott Richman, regional director of the Anti-Defamation League for New York and New Jersey. “That orchestrating of the population — both popular and pernicious — truly ended only in 1968 with the Fair Housing Act.”

Even the website for the Radburn Association itself acknowledges this history of segregated housing. “For at least its first two decades, Radburn systematically excluded as residents virtually all people of color and virtually all Jews,” it says.

“We very clearly have to accept our past,” says Ronald S. Roth, rabbi emeritus at the B’nai Sholom/Fair Lawn Jewish Center. “We should be unafraid to teach what happened here, and also to celebrate that the barriers to us were eventually broken down.”

“Discrimination against Jews in Radburn early on in the 20th century is well-documented,” adds Fair Lawn Mayor Gail Rottenstrich. “Radburn clearly prohibited the sale of houses to Jews for decades. Our town’s 100th anniversary celebration should [have] acknowledged as much. I would be in favor of telling our whole history.”

Attitudes about Jews nationwide post-World War II shifted toward acceptance. Laws against discrimination in housing were enacted and enforced. And, as the country went, so went Radburn. Eventually its Catholic population expanded and the number of Protestants dwindled.

I would have liked to see my hometown make some gesture toward solemn remembrance over the past year, especially as the post-Oct. 7th antisemitic tide continues unabated.

But this didn’t happen. Back in October, Fair Lawn’s 100th anniversary committee discussed acknowledging the issue, but decided against doing so.

Ah, but here’s a happy twist of irony. Soon after World War II, Fair Lawn embraced Jews and evolved into a Jewish stronghold. The town’s population of about 35,000 has remained an estimated 30% to 40% Jewish for at least half a century now, says Rabbi Roth. Nine of its 21 houses of worship are synagogues.

An incident from Fair Lawn HS’s 50th reunion for its 1958 graduating class in 2008 suggests that the wounds inflicted decades ago are slowly healing.

Last year Janet Moss Kass reached out to her older brother Lawrence Moss, who told her what happened at that 50th anniversary event.

A woman unfamiliar to Moss approached him and introduced herself as Ruth Cheney. She said she was happy to see him there because for many years she had carried a burden and needed to apologize.

“For what?” Moss asked.

Cheney then admitted that her own parents were among the neighbors who conspired to buy the house the Moss family planned to buy in 1950 to prevent a Jewish family from moving into Radburn. Cheney recounted overhearing as a 10-year-old the conversations at meetings where her parents and neighbors asked, “What are we going to do?” before resolving to chip in on the $16,000 purchase.

“I always felt it was wrong,” Cheney said. In apologizing, she sought to make amends for a wrong committed by her parents more than 50 years earlier.

“I forgive you,” Moss said without hesitation. “And I forgive your parents, too.”

If only Fair Lawn itself had also seized this anniversary to issue some semblance of an apology.

Bob Brody is the author of the memoir “Playing Catch with Strangers: A Family Guy (Reluctantly) Comes of Age.”