When two former Nazis who worked at concentration camps recently died aged 99 and 100, many believed the atrocities of the Holocaust were finally at an end.

However, a special court in Germany is still pursuing around a dozen of those who helped the Nazis commit mass murder, eighty years after the end of the Second World War, The Post has learned.

“We are always working on new prosecutions,” said Thomas Will, chief prosecutor at the Central Office of the State Justice Administration for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes in Ludwigsburg, just outside the city of Stuttgart.

The special court has helped to find and prosecute some 7,000 Nazi war criminals since its inception in 1958, according to its website.

The court is currently searching for “accessories to National Socialist crimes” born between 1925 and 1927, who were teenage administrators or guards at camps where the murders of more than 11 million people, including the Holocaust of six million Jews, were perpetrated by the Nazis.

But even those cases are getting difficult to prosecute due to the advancing ages. Last month, the last-known Nazi concentration camp guard died before he was set to face German prosecutors for the murder of more than 3,300 people at Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

Gregor Formanek, 100, was a teenager during his employment at the camp and was to be tried as a minor. He would likely have received a suspended sentence if he had been found guilty.

Another teenage Nazi, Irmgard Furchner, 99, was hired as a shorthand typist at Stutthof concentration camp, working there between 1943 and 1945.

In 2021, when she was 96, she was charged with 11,412 counts of accessory to murder. She was the last person to have been convicted in Germany for Holocaust-era crimes and died in January, although her death was only recently announced. She was given a two-year suspended sentence in 2022.

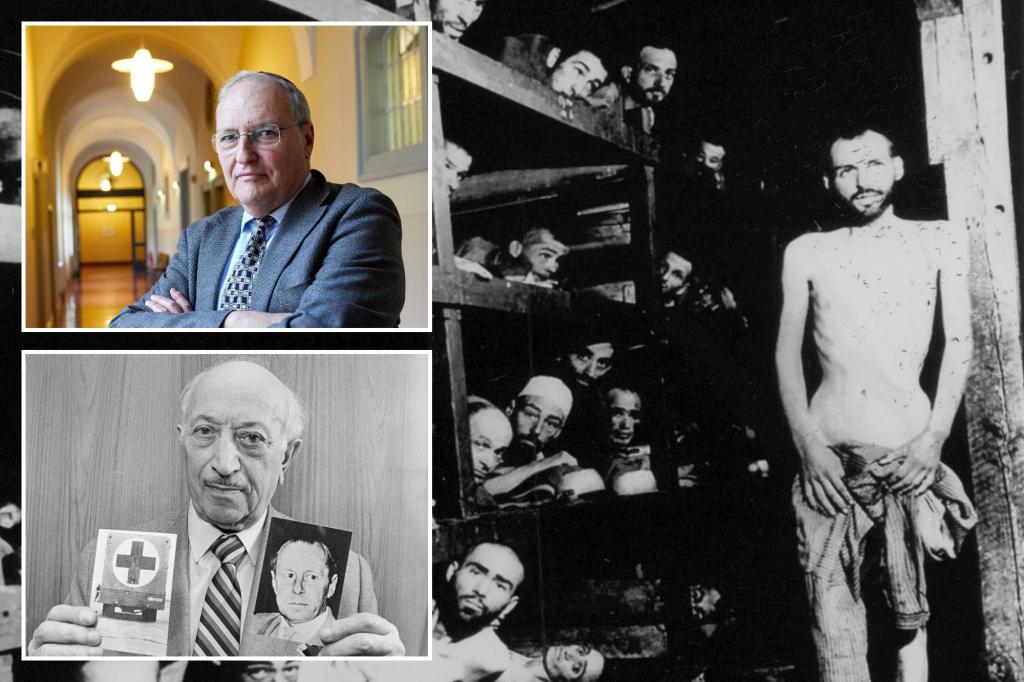

As accessories to Nazi crimes are becoming increasingly difficult to find, one of the world’s most celebrated Nazi hunters has gone into retirement.

But Efraim Zuroff, 76, the New York City-born Holocaust historian who headed up the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Jerusalem, said dozens of former Nazis are still roaming Eastern Europe.

“There are Holocaust criminals in Eastern Europe who have not been prosecuted, since not a single one of the countries which made the transition from Communism to democracy are interested in putting them on trial,” he said.

He told The Post last week officials who helped the Nazis carry out atrocities in Hungary, Lithuania, Croatia, Romania and other Eastern European countries remain at large and have never faced charges.

“Any justice is better than no justice,” said Zuroff. “But right now there is nothing on the docket in Germany, and countries like Lithuania and others did nothing to bring murderers to justice.”

Zuroff’s latest book, “Our People: Discovering Lithuania’s Hidden Holocaust,” is about Lithuania where his maternal grandparents are from. He co-wrote it with Ruta Vanagaite, a Lithuanian writer whose family members were among the perpetrators of the Holocaust in the country.

During their research they interviewed an elderly woman leaving a supermarket and asked her about her time in the war, causing her to break down in tears because her family had decided not to help hide her best friend, a young Jewish girl.

“She told us that they were more afraid of their neighbors than the Germans because the neighbors would tell on them, so they couldn’t hide her Jewish friend,” Zuroff said, adding that his co-writer had to leave the country after revealing hard truths about Lithuanians in the book, which was denounced by the country’s leadership.

However, the lady’s story “was just representative of everything that happened in Lithuania during the war,” said Zuroff, adding “Ninety percent of Jews were killed there.”

Unlike Eastern Europe, the US and Germany were the only countries that actively prosecuted Nazi war criminals, Zuroff claimed. The Department of Justice’s Office of Special Investigations investigated 1,700 suspected Nazis in the US and prosecuted 300.

Zuroff began his career as a Nazi hunter when he joined the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles in 1978. In Jerusalem, where he now lives, he held a leading role in “Operation Last Chance,” a campaign which offered cash for information leading to the conviction of Nazi war criminals. The campaign led to the prosecution of John Demjanjuk, an Ohio autoworker, who was convicted as an accessory to murder at the Sobibor death camp.

Now even in retirement, Zuroff said he is continuing to fight against what he calls Holocaust distortion. He said he is guided by the late Wiesenthal, an Austrian architect who began searching for Nazis right after the end of the Second World War.

Wiesenthal told him although he was not religious, he believed he would meet the victims of the Holocaust in the afterlife and they would ask him what he did to help the victims.

“I’ll do anything possible to fight against Holocaust distortion in countries like Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Croatia, Hungary,” Zuroff told The Post.

“It’s an insult to the victims and the kind of thing that allowed people to say Hamas were the victims of Oct. 7 not the Jews,” he said referring to the terrorist attack in 2023 that left 1,200 Israelis dead.