From the tragedy earlier this month when a Mexican Navy ship hit the Brooklyn Bridge to the German battleship Bismarck having its rudder damaged and eventually sinking after being attacked by the British in 1941, one of the most treacherous issues a military vessel can face is losing its maneuverability.

“This is something that sends fear in the hearts and minds of any sailor,” Montel Williams told The Post.

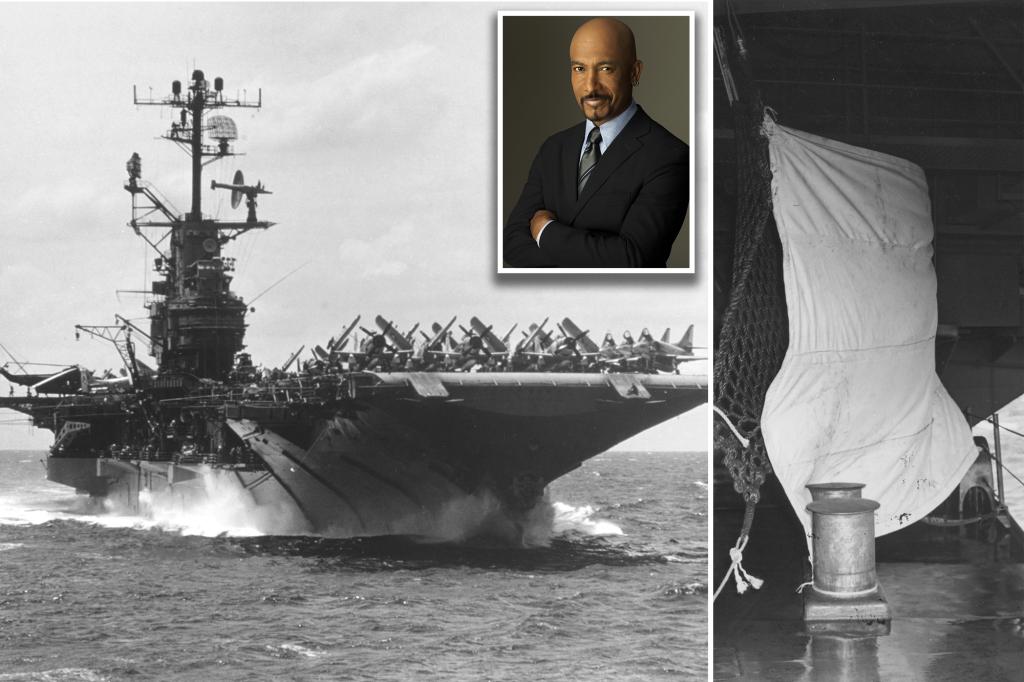

A 22-year veteran of the US Navy and Marines, the Emmy-winning television personality is no stranger to maritime disaster.

In 1981, he was deployed as a special duty intelligence officer on the USS Kitty Hawk in the Indian Ocean when two fighter jets collided on the flight deck. A sailor was killed and an F-14 went overboard in one of the worst peacetime accidents for the time.

“It was devastating,” Williams said.

The experience helped inform his captivating new book, “The Sailing of the Intrepid: The Incredible Wartime Voyage of the Navy’s Iconic Aircraft Carrier,” co-written with David Fisher. It details a little known chapter in the long, storied history of the USS Intrepid, which launched planes during World War II, recovered NASA space capsules in the 1960s and now hosts over a million visitors each year at NYC’s Pier 86.

In 1944, on its maiden combat voyage, the ship was badly damaged in a Japanese torpedo strike. Eleven men died and the ship’s rudder was jammed, sending it careening through what was, at that point, the largest battle group ever staged.

“It was like a ball inside of a pinball machine,” Williams said. “It almost hit the USS Essex.”

The quick-thinking captain and crew came together to hastily assemble a 3,000-square-foot sail to help maneuver the Intrepid 3,300 miles home to Pearl Harbor for repair.

“This most modern ship [for the time] had to resort to the fundamentals of seafaring,” Williams said. “There was this incredible spirit of ingenuity … Instead of saying, ‘there’s nothing we can do, let’s abandon ship,’ they said ‘We’re gonna save this ship.’”

Here, he shares an excerpt.

Initially, much of the crew thought it was a bad joke. They were all concerned about the jammed rudder, but they were confident their officers would figure out some solution. Something technological, the kind of stuff the brass had been taught at Annapolis that was above their pay grade. As much as possible, they just went about doing their jobs. So when they heard a rumor that the captain wanted them to make a sail, they didn’t believe it. “What does he think we’re going to do, sail this ship back to Pearl [Harbor]?”

Another rumor claimed that the radar shack had been warned to keep a lookout for pirate ships appearing on the horizon.

Slowly, the word spread that this sailmaking wasn’t a joke. The captain actually intended to raise a sail and steer the ship home with it. Most of the crew didn’t understand the concept; they visualized Errol Flynn’s popular “Captain Blood,” in which the ship was propelled by numerous white sails billowing in the wind.

It was impossible to imagine Intrepid flying those big sails.

It created serious anxiety. It didn’t make a lot of sense. When they had moved the planes forward and flooded the stern, they sort of understood the reason: redistributing the weight changed the profile of the ship in the water. It made it lower, diminishing the impact of the wind. The captain knew what he was doing. But a sail?

Until that moment, few of them had realized the situation was desperate enough to require a crazy solution. The fact they had to resort to something as wild as this … this … they didn’t know how to describe it, but it meant that they had run out of proven solutions. The news shook up a lot of people. Everybody on board knew the story of Bismarck, how its jammed rudder had led directly to the British sinking her.

Somewhere, deep in their minds, they identified with Bismarck’s crew. They would do whatever it took to avoid that fate.

***

The crew created an assembly line. Pickers handed sheets of canvas to the cutters, who gave them to the feeders — two men facing each other across the worktable — who fed them to Petty Officer Gordon Keith. Dozens of individual sheets of canvas had to be sewed together to form strips several feet wide and almost 30 feet long. Then those strips would be sewed together lengthwise, sort of like sewing the stripes in an American flag. The shop had not been designed to make anything near this size, so they had to figure it out and make the necessary adjustments as the work progressed. For example, two men sat cross-legged under the table to hold up the folded cloth and keep it moving so Keith could continue sewing. Two other sailors, the pullers, stood on the other side of the machine, pulling the now bound pieces until they were free of the table and letting the cloth fold naturally into a pile.

The rhythmic pounding of the machine briefly lulled Keith into the warmth of nostalgia. While his industrial machine made a deeper, more defined thumping sound than the faster, lighter pat-pat-patter of his mother’s home model, for a few brief seconds, it brought him back to those late afternoons when he sat under the vibrating wooden sewing table while his mother made necessary repairs and alterations.

They worked through the night. The shop grew hot and uncomfortable. The fans helped a bit, but more people were crammed into the compartment than had ever been intended. Several men had taken off their shirts, and beads of sweat rolled down their backs. The sewing wasn’t difficult. Singer made a quality machine.

There was little conversation in the workshop beyond “Do you really think this thing is going to work?” That was the question for which there was no answer. Keith was noncommittal. “Well, the Captain thinks so and he knows a lot more about this stuff than I do. Let’s just get it done, then we’ll see.”

“Tell you one thing,” one of the cutters said. “This is gonna make a helluva story one day.” He added with typical doomsday humor, “Assuming we make it, that is.”

****

The sail slowly took shape, although no one in Keith’s crew could accurately describe its shape: sort of like a rectangle but not exactly. Or, think of a big square, then forget that because it definitely was not square.

They finished just as the sun was rising. No one knew precisely how big it was, but in his official reports, First Captain Thomas Sprague reported it was 3,000 square feet. That was a guess. It was far too large to spread out in the compartment to measure. They couldn’t even estimate how much it weighed. Maybe 400 pounds? 500? It easily could have been more. But it was big, bulky, and heavy.

There was a brief discussion about naming it; there was a Navy tradition of assigning nicknames to equipment. The inflatable life vest, for example, was widely known as a Mae West in tribute to that movie star’s legendary figure. A couple of Keith’s crew suggested the sail be referred to as the Rita to honor pinup star Rita Hayworth’s impressive measurements. But beyond a few salacious snickers, it just didn’t catch on. It was “the sail,” “the thing,” or on occasion, “Sprague’s sail.”

Getting it to the fo’c’sle through the narrow passageways, numerous hatches, and up ladders proved to be considerably more of a challenge than anyone had anticipated. As tired as they were, each of them hoisted a section and began carrying it through the ship. They had to carry it, push it, drag it, pull it. All along the route, men popped out of compartments to get a look at it or give some assistance. Frank Johnson later compared it to the Chinese New Year parade he had seen in San Francisco, in which dozens of men inside a dragon costume weaved through the narrow streets of Chinatown.

A swarm of carpenters was already at work when they finally got there. Montfort had solved the issue of the open space on the starboard side in typical ConEd fashion: if you can’t fix it, board it up. He wouldn’t even estimate how many doors and windows in aging buildings he had ordered sealed until potentially dangerous violations could be corrected. The same solution would work in this relatively small space. Board it up. Put up a wind barrier. Carpenters were busy erecting a wooden wall; three lengths of timber stretched horizontally across the opening were holding plywood sheets in place.

Sprague and Commander Richard K. Gaines were waiting in the forecastle with more men to hang it, most of them wearing foul weather gear. None of them had had any idea what the finished sail would look like, but they were disappointed. “That’s it?” one of them said. “Wow.”

They looked to Sprague for guidance. He was doing his best to convey confidence, but the reality of the pile of canvas in front of him made that difficult. “Great job, men,” he told Keith’s crew with as much enthusiasm as he could generate, then went down the line, shaking each man’s hand. Finally, he turned to his crew and said the historic words he had never heard said in his career: “Okay, men. Let’s hoist the sail.”

Adapted from The Sailing of the Intrepid by Montel Williams and David Fisher. Copyright © 2025 by Montel Williams and David Fisher. Published by arrangement with Hanover Square Press, an imprint of HarperCollins.